Aggressively reorienting the forecasting community towards AI resilience

Forecasting is the art and science of putting probabilities to events and updating them as evidence comes in. Depending on how you draw the boundaries, it might have 5-100K people, be a bit larger than the EA community, but more truth seeking, less altruistic, more mercenary, with more tech talent, older.

As you read this, consider the following stylized ambitious project: creating 100 questions on the future of AI on Polymarket, each with $1M liquidity.

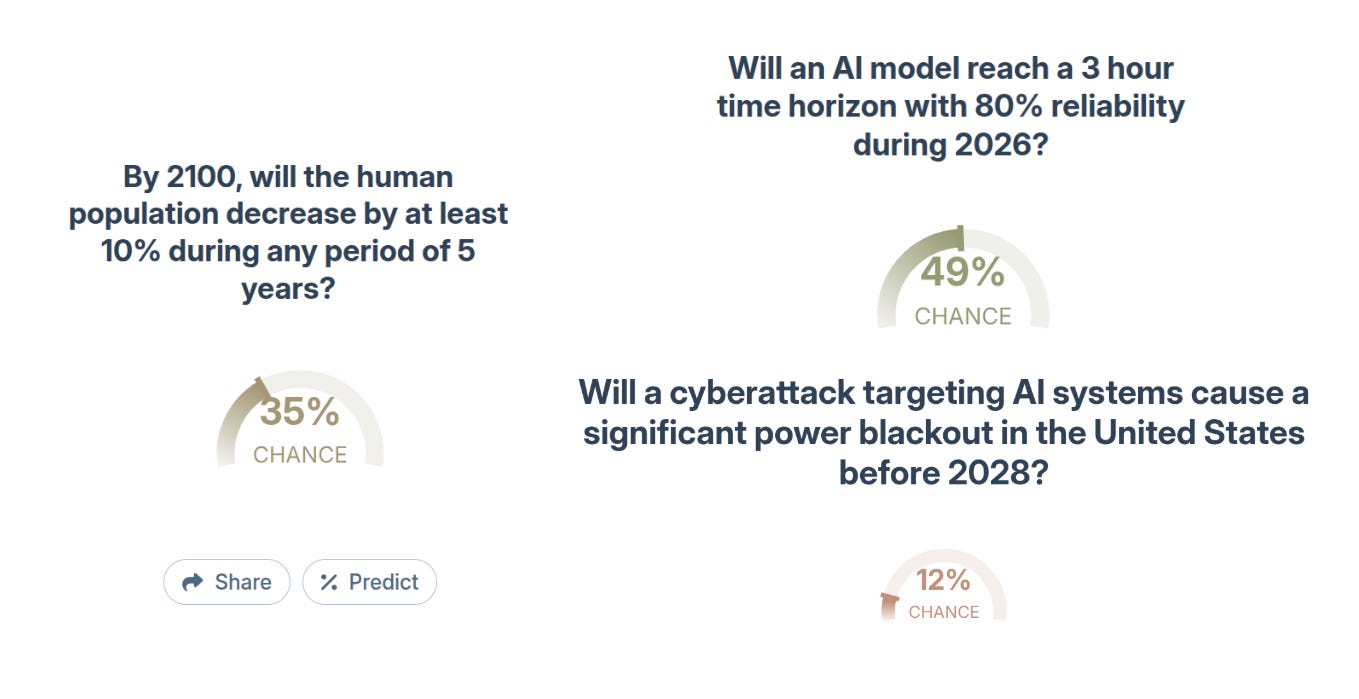

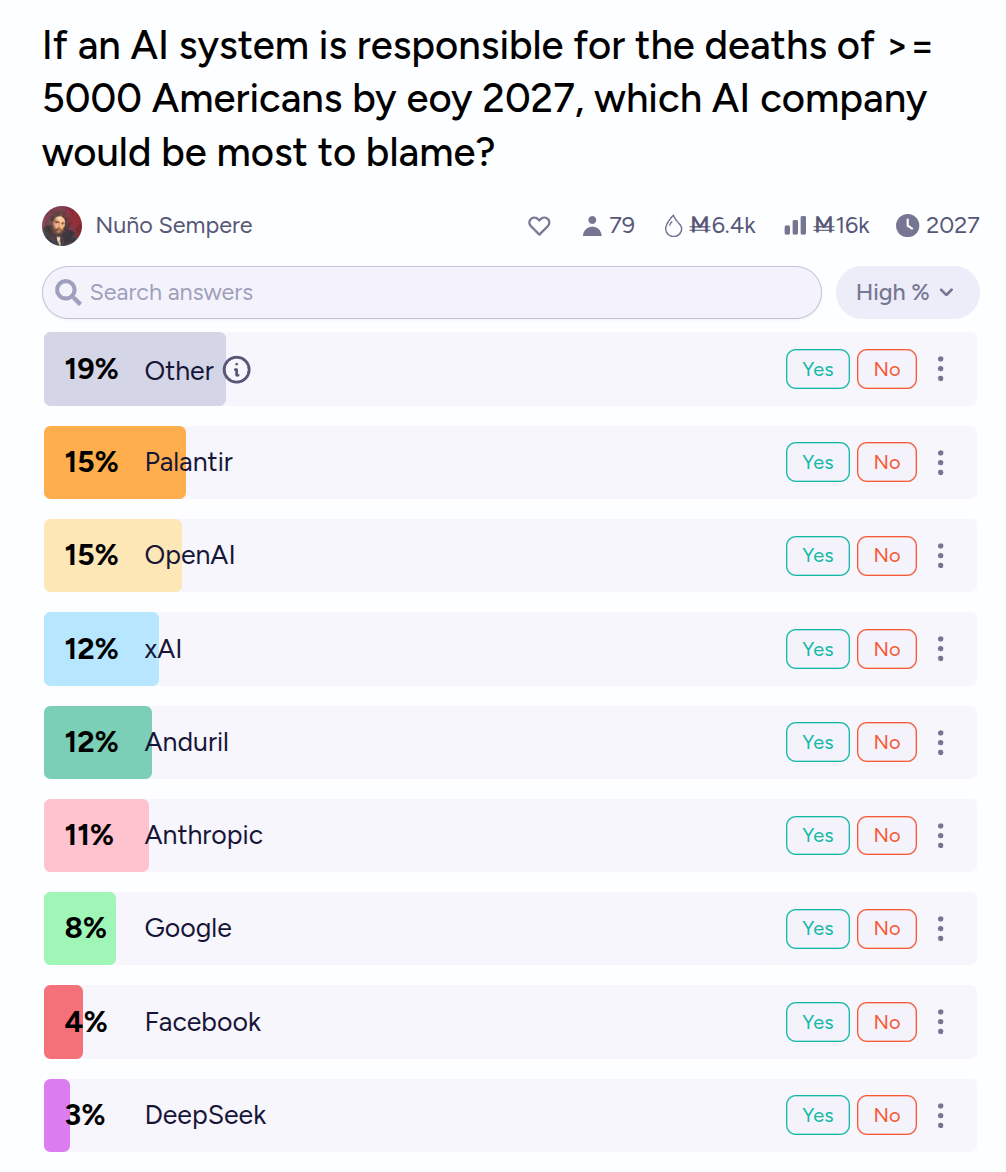

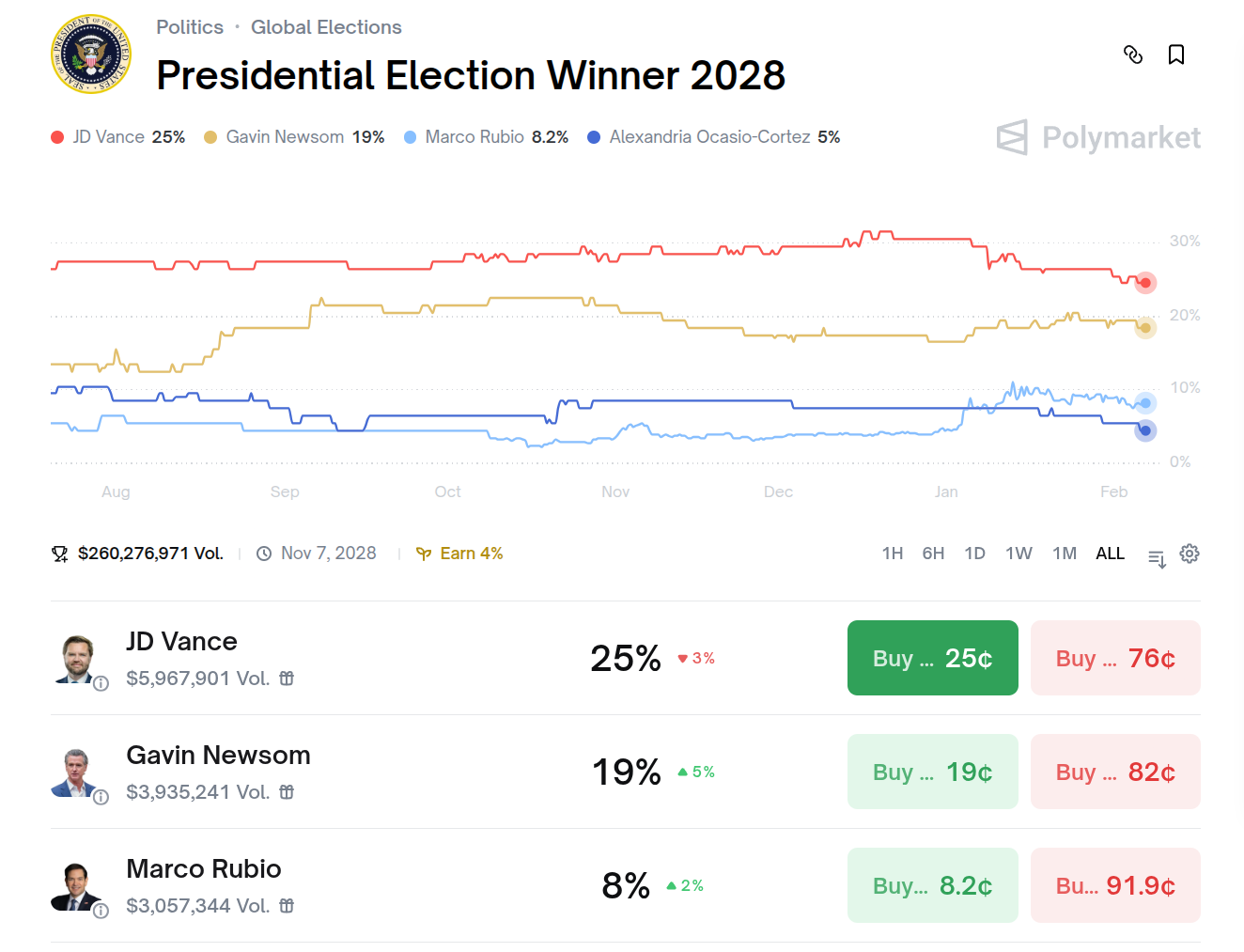

Here are some examples of what the forecasting community can do for you. First, it can give a sense of absolute levels of risk:

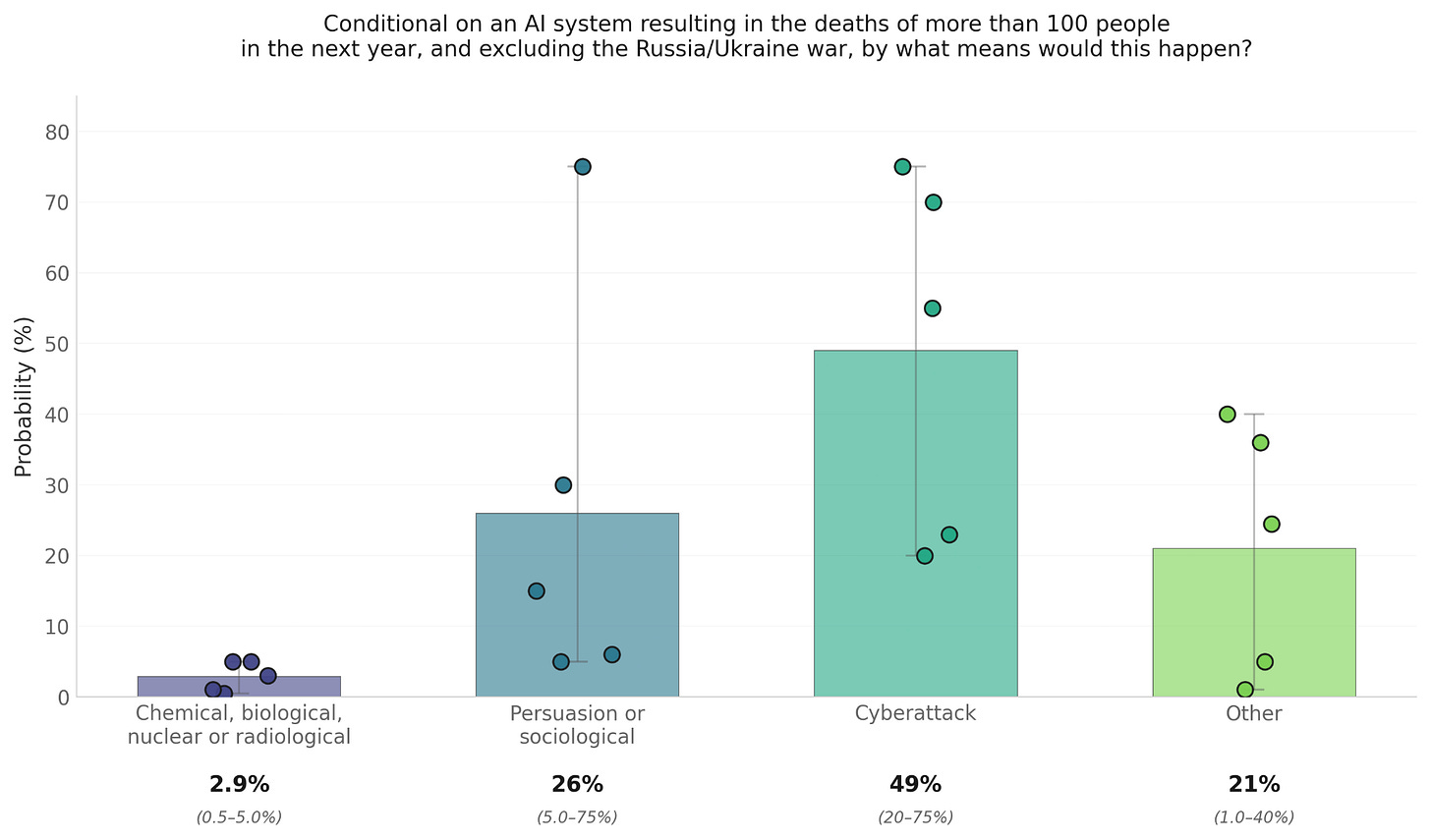

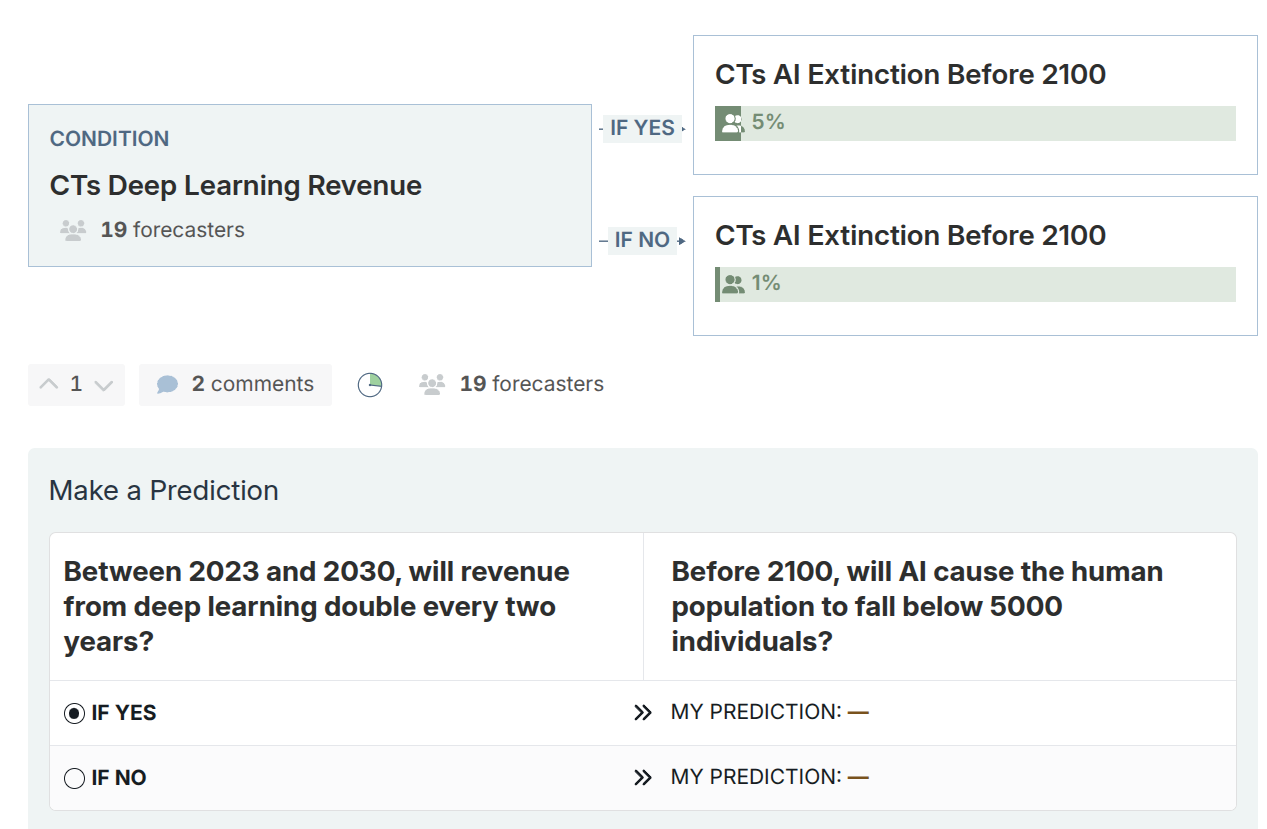

or give a sense of the conditional levels, which avoids people having to agree on what the absolute levels are, and which allow you to prioritize between sources of risk regardless:

These types of probabilities, in addition to being accurate and calibrated, also create common knowledge about the shape of possible futures. $5M worth of volume (at 4% annual interest) plus almost $500K in open interest between 20% and 30% are betting on Vance winning in 2028, weighing many strands of evidence and creating a public synthesis in the process.

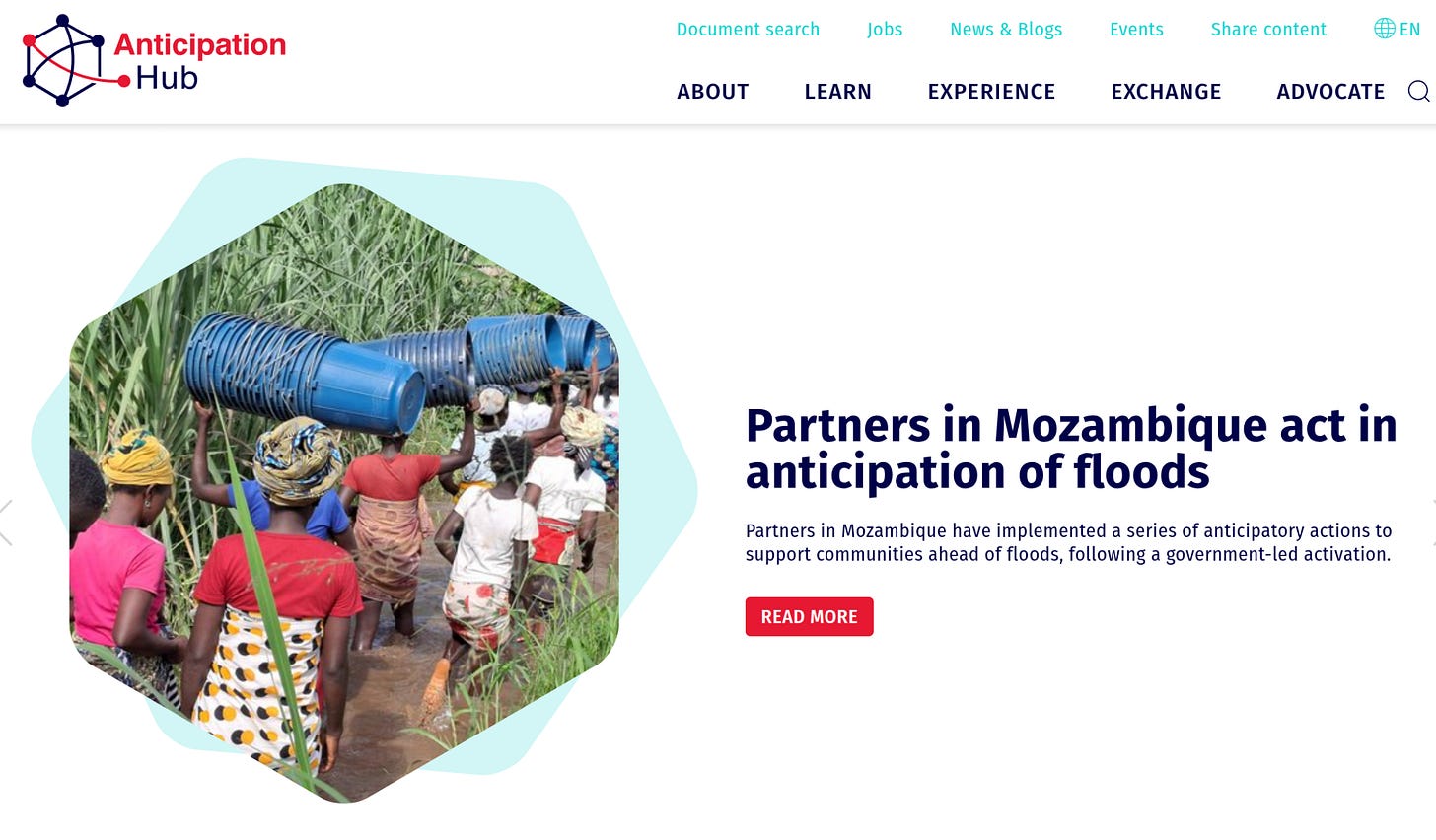

Once one has these trustworthy indicators, they can be connected to action. In the global health context, if you have a weather forecast that indicates there are going to be floods, or a hurricane, you can start preparing your response before the threat hits. AI could have similar mechanisms to deploy mitigations faster.

One nice feature of conditional funding commitments is that they allow you to hedge model error and cover threat models that you don’t believe in. For instance, you might make a funding commitment to unlock $100M once an AI-enabled cyberattack causes over $1B in damages even if you don’t believe that would ever happen. And if you commit to unlocking that funding once a trusted forecast hits 5%, 50%, 75%, you can react before it actually happens, potentially long beforehand. Similarly, if a major insurer offered catastrophic insurance, for instance at 5cts on the dollar, this could also allow organizations concerned with threats, such as my own, to be more well-ressourced in the event of a catastrophe.

Conversely, the ability of forecasting to create common knowledge also brings dangers, because there is the temptation of using it essentially as propaganda, by having leading questions, selecting a population of forecasters that is sympathetic to your perspective, and simply ellicit probabilities rather than having participants have skin in the game. But here be dragons.

The forecasting community is also, ironically, very acquainted with the limits of foresight. One limit is around how far into the future one can forecast. As time goes on, the amount of factors that one hasn’t considered stack up, and the chance that one of them ends up being decisive rises. For geopolitics, the threshold at which it is hard to make good forecast might be a few years. But for a rapidly changing field, like AI, this might be much shorter.

In geopolitics, one striking event in the last few years was Prigozhin (head of the Wagner group) marching with his tanks towards Moscow and then turning back. He then got disposed of in a helicopter accident soon afterwards. This turn of events was surprising to me personally: I didn’t foresee the possibility of a revolt, and then once it started I didn’t see Prigozhin simply giving up, because he’d just get killed (as he did). Similarly, the specifics of moltbot and moltbook seem very hard to foresee long beforehand with much precision. Consider that the correct hypothesis might not be in your hypothesis space.

There are two immediate suggestions to draw from this. The first one is to not rely too much on a named list of threats, since you might find that the actual threat wasn’t in your hypothesis space. Threats specifically seem somewhat anti-inductive: if you expect most of the danger to come from e.g., AI enabling biological weapons, you might invest in enough mitigation measures that you bring the attractiveness of bioweapons down for a possible attacker, so he chooses something else.

A second suggestion is to invest in rapid response in addition to mitigation. If you take seriously the possibility that you will not see the shape of a threat until very shortly before it arrives, it might make sense to invest in being able to deal with types of emergencies you haven’t seen before.

A second limit of foresight is it doesn’t matter how good your foresight is if you don’t connect it to actual decisions. See Cassandra above pulling her hair because she saw Troy burning happening but could do nothing about it. To avoid this pitfall, forecasters are generally extremely happy and motivated to forecast on questions they know will be used for important decisions, so perhaps an ask would be for access, to connect forecasting questions to decisions and announce this beforehand.

Earlier, I mentioned the idea of adding $1M of liquidity to 100 questions on Polymarket. There is probably something hypnotic to me about those numbers. I think doing so would improve society’s ability to orient around AI. Pundits and publications throwing shade on AI progress would be able to better update if money was on the line. Conversely, over-optimistic cheerleaders would be able to restrain their enthusiasm in time if they are wrong. I think that intervention meets some internal bar for worth doing in the presence of abundant funding.

My own org, Sentinel, is also doing some work in the space of forecasting risk, though not only from AI. We are processing millions of news items, 20-40K subreddits and hundreds of twitter accounts each week to search for signals of large-scale catastrophes. We estimate probabilities of the top risks on a weekly basis, and do ad-hoc engagements on specific risks.

But I don’t think Polymarket (or Sentinel) is the most efficient way to spend $100M to re-orient the forecasting community around AI, although it is a scalable intervention. It would be more efficient to be more surgical about it. Here are a few forecasting or forecasting-adjacent organizations I’d be excited about empowering more; they could do a good job for less than $100M.

I will leave further discussion for past and future posts, but hopefully I’ve gotten the idea across that perhaps the forecasting ecosystem could be fruitfully leveraged.

Good article!

> He then got disposed of in a helicopter accident soon afterwards.

It was a private jet, with the other Wagner executives on board, leaving Moscow; likely a bomb at 28,000 feet. I found it clarifying.

He simply stopped the March on Moscow after destroying five RAF aircraft, and a few weeks later was traveling around Russia like nothing had happened, while Kremlin spokesman Peskov said "No, we are not tracking his [Prigozhin’s] whereabouts, have no possibilities and desire to do so". That seemed weird, but Prigozhin was a propaganda king first and military leader second. Evidently he viewed his March on Moscow as part of that theatre, and then Putin worked to convince him, falsely, that the two of them had come to an understanding. (I'm sure Prigozhin also knew the march was very risky, but the Kremlin was sidelining him by absorbing Wagner into MoD, which was also risky for him.) Perhaps the intended audience of Peskov's quote was precisely those executives on the plane.

When I have the cash I'll cut you a check.